We are thrilled to welcome author James W. Ziskin! Novels in his critically acclaimed Ellie Stone series have been Anthony and Macavity award winners and Edgar, Anthony, Barry, Lefty, and Macavity finalists. Read on for a fascinating discussion of how he works with language in his latest mystery, TURN TO STONE, which is available now.

Foreign Words in Foreign Lands

I write a series of traditional mysteries set in the early 1960s, featuring a plucky young newspaper reporter named Ellie Stone. Ellie is a self-described “modern girl.” That means exactly what you think. She smokes and drinks and sometimes ends up in the arms of a man she has no intention of marrying. But Ellie’s also a highly empathetic soul with a strong moral compass. And she’s ambitious, demanding a turn at the table at a time when women weren’t usually welcome in the workplace.

Ellie left her native New York City for a newspaper job in an upstate New York mill town because she wanted a career and this was her only offer. Placing her in the small town of New Holland, NY, created a Cabot Cove Syndrome problem for the series. You know, that disorder characterized by too many murders in a small village? To avoid that, I’ve kept her on the move. Ellie has solved crimes in New Holland, New York City, the Adirondacks, Los Angeles, Saratoga Springs, and now—in the latest installment, TURN TO STONE—in Florence, Italy.

It’s September 1963. Ellie is in Florence to attend an academic symposium honoring her late father. Just as she arrives on the banks of the Arno, however, she learns that her host, Professor Alberto Bondinelli, has been fished out of the river, quite dead. Then a suspected rubella outbreak leaves ten of the symposium participants quarantined in villa outside the city with little to do but tell stories to entertain themselves. Making the best of their confinement, the men and women spin tales and gorge themselves on fine Tuscan food and wine. And as they do, long-buried secrets about Bondinelli rise to the surface, and Ellie must figure out if one or more of her companions is capable of murder.

Setting the action in a foreign country presents certain challenges not present in “domestic” stories, the most obvious being the language problem. Does our heroine speak the local tongue? Are there translators and interpreters to help her along? Does she rely upon the kindness of strangers to point the way to the biblioteca?

In Ellie’s case, she has a long and complex history with the Italian language. Her father was a celebrated scholar of Italian literature—in particular, Dante. He spoke several languages well, Italian best of all. Ellie learned a good deal of Italian as a young girl, which, by the way, is the best time to learn any language. The earlier the better. Somehow the brain and our speech apparatus have more success with second-language acquisition when we start at a very young age. Even if children don’t learn all the vocabulary that they will need later on, they can still master elements such as pronunciation and grammatical structures. Vocabulary can be learned anytime, but a perfect accent usually eludes adult learners. Not so young children. Ellie had the advantage of learning as a small girl and, therefore, had a great head start.

For her trip to Italy in TURN TO STONE, she took private lessons for ten months before her departure. Her nosy landlady’s aunt, a nun originally from Naples, helped Ellie improve her Italian significantly. Interestingly enough, Sister Michael inadvertently imparted traces of her native Neapolitan accent to Ellie, as one of her new friends in Florence points out.

So Ellie’s Italian is highly functional by the time she arrives in Florence in September of 1963. The term “fluent” gets tossed around quite freely; language is a large and slippery beast. To master it takes years and years and devotion and practice. I’ve made a career out of studying languages: Italian, French, Spanish, German, some Hindi, and, of course, English. While some (read most) people hate grammar, I love it. Its logic, exceptions, and history are at the heart of its beauty.

Ellie is what most people would call “fluent” in Italian, which doesn’t mean there aren’t holes in her language skillset. She experiences occasional communication breakdowns in Italian and resorts to her native tongue. There are lots of words she simply doesn’t know because she didn’t grow up in Italy. This is common among all foreign language learners. In my case, for example, the names of flowers and obscure animal species are not my strong suit in Italian. Some foods, too. If you’re a picky eater, you’re probably not going to be able to translate the entire menu without help. But these are specialized vocabulary. For anyone who fancies herself fluent in a foreign language, imagine you had to translate Moby-Dick without a dictionary. The seafaring and whaling terms alone would stump even the most talented UN translator. So let’s accept that Ellie speaks Italian very well—exceptionally so in social situations— but she is not quite at the level of an educated native speaker.

That’s how Ellie gets by during her visit to Florence. It spared me, the writer, a lot of headaches in my work. If Ellie constantly needed an interpreter, that would have been awkward. Or, if the others all spoke passable English to accommodate her ignorance, that would have strained credulity. At least mine. In 1963, fewer Italians spoke English well as compared to today. English has become an essential skill for anyone in business, the arts, and travel. It’s the official language of air traffic control the world over, after all. All air-traffic controllers and pilots speak English to each other on the job. From my own experience, I see a vast difference between the level of English spoken throughout Europe today compared to forty years ago when I was first traveling the Continent. Don’t be fooled by the old movies. You know, the ones where Katharine Hepburn visits Venice and meets Rossano Brazzi. He speaks what seems to be perfect English. But if we listen closely, we get the sneaking suspicion that he probably doesn’t understand the words he’s memorized. And then there’s the clichéd street urchin who has picked up English somewhere. He speaks remarkable well, possesses a rich, complex vocabulary, but somehow doesn’t know the English word for “yes.” Isn’t “yes” the first word one learns in a foreign language? But cute little kid always says “sì” or “oui,” depending on which culture is being stereotyped.

I kid, of course. But only a little. I wanted to avoid these clichés in TURN TO STONE, and Ellie’s excellent Italian allowed me to do so. Still, there’s the problem of how to present the dialogue in the book. If a conversation takes place in Italian, you can’t exactly write it out in the original then translate it. Readers would revolt, throw the book against the wall, or worse, at the cat. No, in such situations we have no choice but to write the dialogue in English with the tacit understanding that the characters are actually speaking Italian. And to drive that point home, it’s sometimes useful to pepper the dialogue with a few foreign words and phrases, n’est-ce pas?

Problem solved! Or is it? How much is too much? As with pepper, one should be judicious when adding it to the soup. After much consideration, I’ve come up with two rules in this regard. 1.) Use words and phrases that are easily understood in context by the reader and/or 2.) Translate them in a natural, unobtrusive manner for the reader. Cognates—words from different languages that resemble each other closely—are a good way to add some foreign flavor to dialogue. In TURN TO STONE, I used “Ispettore Peruzzi” many times. Even readers who don’t know a word of Italian are sure to understand that this means “Inspector Peruzzi,” especially when considered alongside descriptions of the man as a police detective. Then there are the well-know Italian words that most people are familiar with already. A few of those help set the scene. Grazie, buongiorno, signora, arrivederci, ciao, etc., are good examples. It’s customary, by the way, to put these words in italics to indicate they are foreign terms. But if they’re common enough to appear in English dictionaries—like “taco,” for instance—line editors tend not to italicize them.

Here are some examples of how I handled foreign words in TURN TO STONE.

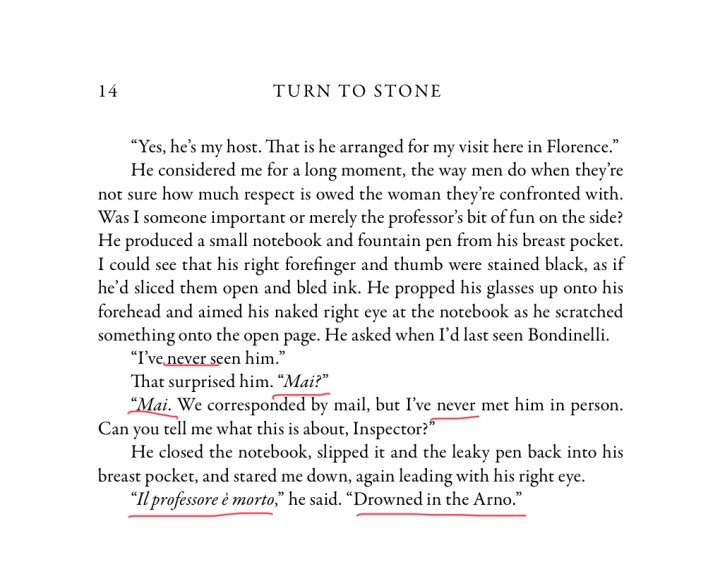

1. Ellie meets the police inspector, who asks her about Professor Bondinelli. He asks when she last saw him, to which she replies that she’s never seen him. He’s surprised and asks, “Mai?” By context, the reader should understand that “mai” means “never” in Italian. Next, the inspector tells her that her host, Bondinelli, has drowned in the Arno. When the dramatic revelation comes, I decided to deliver it in Italian. “Il professore è morto,” he said. “Drowned in the Arno.” I believe that most readers will recognize “professore” and “morto.” But even if they don’t, the very next sentence in English makes it clear what has happened. He’s drowned in the river.

2. When Ellie is lunching with her late father’s last student, Bernie Sanger, they reminisce about his linguistic tics and peculiar usages. These involve Italian, German, and French. When Ellie explains that he used to ask her opinions on things using “Was sagst du?” and “Qu’est-ce que tu en penses?” there is no need to translate. She’s already told us what he was asking.

3. Another example from Ellie’s lunch with Bernie includes a difficult Italian word that almost no reader would know. “Segatura” is Italian for “sawdust.” I solved this problem by having Ellie say the word in Italian and Bernie translate it in natural conversation, as if asking for confirmation.

4. Later in the book, as Ellie questions someone about Bondinelli’s wartime past, I used the term “mutilato di guerra” without translation. But the context clearly indicates that he—Bondinelli—was wounded (mutilato) in war and, therefore, could no longer serve in the army.

5. Finally, foreign words and expressions can make for some fun, clever puns or turns of phrases. When Ellie meets a wild boar on the grounds of the villa in Fiesole, she describes the danger with a couple foreign terms thrown in for effect. She makes clear that “cul par-dessus la tête” is the French equivalent to “head over heels.” But how much more fun is it if readers understand that “cul” actually means “rear end” in French? And the reference to tusks in Italian is referring back to earlier scene when the word first came up. “Zanne” is another one of those uncommon words Ellie would not have known otherwise, despite her excellent Italian.

There are a few shortcuts and tricks that can be used to introduce foreign words and dialogue without resorting to clumsy, literal translations from the author. I’ve tried to give the flavor of the Italian setting by sprinkling these terms throughout the text. By doing so, I hope the reader will subconsciously absorb some of the setting without being frustrated and bored by the unknown words.

TURN TO STONE is in stores and online portals January 21, 2020.

James W. Ziskin, Jim to his friends, is the author of the seven Ellie Stone mysteries. His books have been finalists for the Edgar, Anthony, Barry, Lefty, and Macavity awards. His fourth book, Heart of Stone, won the 2017 Anthony for Best Paperback Original and the 2017 Macavity (Sue Feder Memorial) award for Best Historical Mystery. He’s published short stories in various anthologies and in The Strand Magazine.

James W. Ziskin, Jim to his friends, is the author of the seven Ellie Stone mysteries. His books have been finalists for the Edgar, Anthony, Barry, Lefty, and Macavity awards. His fourth book, Heart of Stone, won the 2017 Anthony for Best Paperback Original and the 2017 Macavity (Sue Feder Memorial) award for Best Historical Mystery. He’s published short stories in various anthologies and in The Strand Magazine.

Before he turned to writing, he worked in New York as a photo-news producer and writer, and then as director of NYU’s Casa Italiana. He spent fifteen years in the Hollywood postproduction industry, running large international operations in the subtitling and visual effects fields. His international experience includes two years working and studying in France, extensive time in Italy, and more than three years in India. He speaks Italian and French. Jim can be reached through his website www.jameswziskin.com or on Twitter @jameswziskin.

This attention to detail makes the readers feel like they took a vacation.(and try taking a vacation as cheap as a book!)

LikeLiked by 5 people

No passport or ticket needed, Etta! 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

Jim, what a great adventure, taking Ellie to Florence! And the way you deftly weave Italian phrases into the story adds to the romance and excitement of the setting! Congrats, and thanks for visiting with the Chicks!

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks, Vickie! It was a pleasure.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Sounds like you put a lot of thought into how to handle the language barrier for a novel. I’m sure it will pay off for the readers.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks, Mark. Hope so!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jim! *waving madly* I’m a big fan of Ellie and your description of language rules. I barely know English, so there won’t be any foreign languages in my books. Although, just yesterday I was going over my editor’s notes and saw both of us failed to italicize “wunderkind.” But when I checked, it was one of those words like “taco,” common parlance now.

Thanks for visiting us here! Great post.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks, Becky! And you’re right. Wunderkind would not be italicized in English. We’ve borrowed it from German, and we’re not giving it back!

LikeLiked by 4 people

I was kinda hoping it meant I was bilingual. Trilingual if you count my vast knowledge of Mexican menus.

LikeLiked by 2 people

LOL, Becky. You got me with the last word in that sentence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Language and grammar nerd that I am (I seem to recall that that’s how we first met, Jim, discussing arcane aspects of linguistics over cask-conditioned bourbon at the CCWC bar some years ago), so I love this piece! It’s wonderful how you manage to work explanations for your foreign phrases into the text without being pedantic. E che forte che la storia sia ambientato a Firenze! (Can’t remember the HTML for italics–scusate!)

LikeLiked by 3 people

Ciao Leslie! Ah, yes. I remember it well. CCWC. You were drinking Bourbon, but I was drinking Dewar’s. 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jim, this is great! The characters in my new series are Italian and I’ve been doing a little of what you’ve been doing. Letting words stand where they’re self-explanatory and finding a creative way to insert translations when necessary. For me, the problem has always been that my mother spoke a dialect, so sometimes the way I spell an Italian word is a total headscratcher to the rest of the world!

LikeLiked by 5 people

Thanks, Ellen. For your book, you can always check the dictionary for the standard Italian spellings. In bocca al lupo!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fantastic post, Jim! You handle the nuances of language so beautifully!!

I especially loved what you said about true fluency and authenticity. It reminds me of my first day with a host family in France, during which I said “zut alors!” Evidently my 9th grade French was a few decades behind the times. (My host family did get a good laugh out of it!)

Thanks so much for visiting, and many congratulations on your success and the latest in this wonderful series.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much, Kathleen! Lucky for me, outdated Italian fits the time period of this book perfectly!

LikeLiked by 3 people

My French teacher taught us zut alors too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Too funny! My French “family” said it was akin to saying “Zeus’ trousers!” I think they were teasing, but it made me laugh. 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

HA HA!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post, Jim, and thanks for visiting Chicks today! I was lucky enough to begin learning French in second grade, courtesy of a public school system from a bygone era. Think maybe we took Madame’s daily classroom visits for granted at the time, but later I was very grateful. I hope to pick up a few handy and zesty Italian phrases from reading TURN TO STONE–it sounds favoloso!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks for having me, Lisa! It was a pleasure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is so fascinating. Lucky students who have had the opportunity to take a class from you!

As I read the book, I so admired the way it felt authentically grounded in the setting (among so many other fabulous things, of course). Your thoughtful explanation here sheds some light on how carefully you fashioned your text. It’s inspiring.

Congratulations on another wonderful addition to the Ellie Stone series and thank you for visiting us!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much, Cynthia, for having me. It was a pleasure. I know the post was a little long. But once I start about language, it’s hard to get me to stop.

LikeLiked by 3 people

It’s so interesting!

LikeLike