Jen here, and I’m happy to have Delia on the blog. We’re now imprint sisters at St. Martin’s, and I love the wealth of knowledge she’ll be sharing today. Delia has been able to switch voices in her writing with great skill. Check out her tips below!

Switching Voices

Delia Pitts

When I started writing my latest mystery, Trouble in Queenstown, the voice of private investigator Vandy Myrick jumped into my head with two lug-soled boots. She sounded confident, tough, pissed off, and gut-punched by unimaginable grief. The central character in my previous mystery series, SJ Rook, was a different sort of guy. Mainly because he was a guy.

So, how did I make the switch from writing a contemporary noir story featuring a male character to crafting a female first-person voice for a small-town murder mystery? With lots of care and chocolate.

Being a woman didn’t necessarily help because I was determined to make Vandy sound and behave quite differently from me. So, I made her an ex-cop and a gym rat boxer with a nasty left jab.

To differentiate Vandy’s POV from Rook’s, I looked at four broad categories of character development: language; physicality; accessories, and intimacy.

Language: I embraced the tropes around men to deprive Rook of a layered vocabulary about clothing, colors, furniture, and emotions. He describes footwear as just shoes, whereas Vandy easily refers to designer pumps, ballet flats, and kitten-heels. I made Vandy hyper-feminine in at least this realm; she employs a dozen variations on white to describe the colors in her magazine-ready home. And though she can be terse even coarse at times, Vandy values a well-crafted poem or other literary reference.

Physicality: Here, I challenged some of the standard cliches about private eyes for both of my lead characters. I made Rook tall, dark, and good-looking, sure. But I gave him a disabling combat injury and a permanent limp. No swagger, no man-spreading, no power bark, no dominating the room. Rook recedes into the shadows by temperament and style.

With Vandy, I went for the opposite. She is a rangy attention-grabber who commands every space she enters with her muscular curves and powerful stride. Effortlessly sexy, she’s a capable boxer, a graceful athlete who uses garden tools for impromptu weapons.

As a Black woman, Vandy is aware of the microaggressions that plague her daily existence. She’s super cautious in her encounters with police. She notes how often her opinions are overlooked when advancing her theory of the case. She knows she’s underrated because she has an alluring figure. Leaning into the portrayal of these microaggressions strengthened my development of Vandy’s character and enhanced the verisimilitude of her world.

Accessories: Unlike his fictional PI counterparts, Rook has no car, a meager diet, and paltry wardrobe. Most importantly, Rook doesn’t wield that defining symbol of American masculinity, a gun. Vandy shares Rook’s aversion to guns. But her reasons are emotional, rooted in a recent family trauma.

Though they both dislike guns, Rook and Vandy differ on another core private eye accessory – adult beverages. Rook won’t let an afternoon pass without one bourbon on the rocks. Not Vandy, who has sworn off alcohol; she makes her bartender concoct elaborate mocktails instead. Displaying iron discipline, she’s a regular in her hometown local, but never sips the hard stuff.

Intimacy: Both Rook and Vandy are single. But the similarity ends there. Views on sex and friendship, interactions with work colleagues and bosses, relationships with parents and children. All of these were areas in which I could draw sharp contrasts between my two lead characters, helping me to switch to a female voice for my second series.

As elsewhere, my main guy and gal don’t always run in the expected gender lanes. No string of gorgeous girls hangs on Rook’s arm. From the start, he is a one-woman man, a Tess Trueheart in trousers.

Vandy, on the other hand, is randy. She often prowls her favorite bar looking for one-night stands and finds willing men with ease. Giving Vandy a vigorous sex life helped me develop a distinctive feminine voice for my lead character.

To break with the standard PI set up of lone, self-employed, wolf, I gave each lead two work partners. Rook is low man on the totem pole in a detective agency run by a father-daughter duo, where he falls hard for his beautiful boss.

Vandy works on retainer in the law firm of her best friend. The two women are supported by a glam girl admin assistant – who is married to the lawyer. Embedding Vandy in this office setting allowed me to vary the female voices of the novel.

For writers: how do you use the dimensions of language, physicality, accessories, and intimacy to craft voice for your books?

For readers: what novels have you read recently which use these elements to memorable effect?

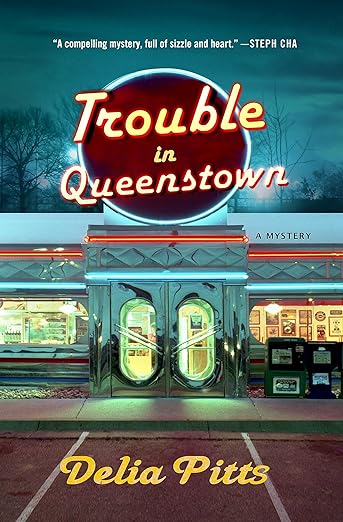

ABOUT TROUBLE IN QUEENSTOWN:

Evander “Vandy” Myrick became a cop to fulfill her father’s wishes. After her world cratered, she became a private investigator to satisfy her own expectations. Now she’s back in Queenstown, New Jersey, her childhood home, in search of solace and recovery.

To keep the cash flowing and expand her local contacts, Vandy takes on a divorce case for a new client — the mayor’s nephew, Leo Hannah. At first the surveillance job seems routine, but Vandy so realizes there’s trouble beneath the surface when a racially charged murder with connections to the Hannah family rocks “Q-town.” Fingers point. Clients appear. Opposition to the inquiry hardens. And Vandy’s sight lines begin to blur as her desire to uncover the truth deepens. She’s a minor league PI with few friends and no resources, but with a determination few possess — she’ll stop at nothing to solve this case.

PRE-ORDER LINKS:

Bookshop.org: https://bookshop.org/p/books/trouble-in-queenstown-delia-pitts/20345038?ean=9781250904218

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Trouble-Queenstown-Delia-Pitts/dp/1250904218/ref=monarch_sidesheet

Barnes & Noble: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/trouble-in-queenstown-delia-pitts/1143881761?ean=9781250904218

ABOUT DELIA:

Delia Pitts worked as a journalist before earning a Ph.D. in history from the University of Chicago. After careers as a U.S. diplomat and a university administrator, she left academia to write fiction. Trouble in Queenstown is the first book in a new mystery series featuring Black private investigator Vandy Myrick. Delia is also the author of the Ross Agency Mysteries, about a Harlem detective firm, and several acclaimed short stories. She is a member of Sisters in Crime, Mystery Writers of America, and Crime Writers of Color. She and her husband live in New Jersey, while their twin sons are Texas residents. Learn more about Delia at DeliaPitts.com.

CONNECT WITH DELIA:

Threads: @deliapitts50

Instagram @deliapitts50

Website www.deliapitts.com

Jim Duncan is very much a no-nonsense kind of cop – just the facts ma’am. At least when he’s working. He shows a more sensitive side to his girlfriend. That’s Sally Castle, who uses a few more words to tell a story. But I can’t say Jim doesn’t notice the details. He does, which is what makes him a good investigator. But yes, he’s much more likely to say a thing is blue not cerulean, like Sally would.

Betty Ahern has a competely different voice. She’s young, only has a high school education, uses the street slang of her times, and has a bluntness about her. Just tell the truth. But she has a softer side I hope readers see, especially now she’s torn between the man she’s engaged to (who is overseas and doesn’t necessarily support her choice to be a detective) and the man at home (who is gorgeous, supportive, but who is a conscientious objector to the war, something not well supported in WWII).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Love the different voices you have through Jim and Betty!

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is an excellent portrayal of how contrasting male and female voices blend to enhance the story. Thank you for sharing, Liz!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Delia,

I like how you’ve created two very different PIs. In my books, the POV character is a female, but most of my short stories are written from a male investigator’s viewpoint. I have to say I use language and observation to craft the different characters. Stefanie Adams has a more involved inner dialogue than Michael St. Killian, and notices a broader range of details about the people she interacts with. St. Killian has a more focused approached, both in what he observes about his targets, and in his conversation. Somewhat along the lines of the generality of males being “hunters” and females being “gatherers,” in terms of their approaches to challenges.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Didn’t mean to post anonymously. I need more coffee!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting that you switch viewpoints in books versus short stories. Is that a deliberate choice, Mary?

LikeLike

It is, but only in that a particular story calls for a particular main character. I won’t rule out a future book with a male protagonist or a short story with a female protagonist.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mary, I love your point about the differently layered interior conversations for male and female characters!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for visiting today and sharing this writing gold, Delia! Cheers!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had a blast teasing out the differences between my approaches to my main characters. I learned more about them — and my writing techniques — as I dug into this essay!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Delia, this is such a wonderful articulation of how to differentiate characters. I’m going to keep all of this in mind as I describe some supporting characters in my current manuscript! Thanks so much for guesting with us today.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you, Ellen! I had such fun trying to articulate how I make these characters come to life.

LikeLike

Thanks for being a guest today, Delia! Writing 3D characters with different voices is always fun–and a bit challenging. I’ll be looking over your tips again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jen, thank you so much for inviting me to join the always-lively conversation here at Chicks on the Case! I had fun and learned a lot too!

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is fascinating, Delia! I love how you set out the differences in character attributes between the main characters in your two series–a lot to learn from this! Thanks so much for visiting the Chicks today to share all this knowledge with all of us!

When I started writing my second Orchid Isle series, I was worried that Valerie’s voice would be similar to that of Sally Solari–even though Val is twenty years older than Sally, and a lesbian, to boot. So I decided to change from the first person to the third in MOLTEN DEATH, which did a good job of switching my brain away from Sally and to this entirely new character. But as you point out, there’s so much more to consider–language, physicality, relationships….

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s a good point about switching from first to third person to differentiate!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Leslie, thank you for including me in the gang today! As you note, it is so hard to carve out different voices for these characters who invade our minds to tell (shout) their stories!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Delia, thank you so much for visiting us! I love this post so much. Compelling writing really is in the details, especially when crafting character and voice. Your intentionality and dedication to digging into differentiators are inspiring!

LikeLike

Thank you, Kathleen! I loved diving into the details that make my characters unique and memorable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Kathleen, for your thoughtful comment. I loved delving into the often minute details of my characters to give them dimension and authenticity.

LikeLiked by 1 person